Why 'Adjacent' Matters: How Collaboration Architecture Shapes System Design

Why I chose 'adjacent' over 'augmented' and what it means for human-AI collaboration. The philosophy behind the framework.

In 1962, Douglas Engelbart published "Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework." His vision wasn't artificial intelligence—it was intelligence amplification. The distinction matters more today than ever.

Most AI tools promise to do things for you. They'll write your code, answer your questions, automate your workflows. The implicit assumption: human effort is overhead to be eliminated.

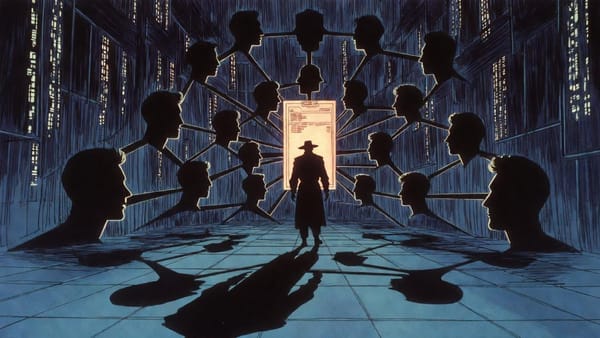

I built something different. The Intelligence Adjacent framework treats AI as a collaborator that works alongside human intelligence—not inside it, not replacing it, but adjacent to it. The geometric metaphor is deliberate: adjacent entities share an edge while maintaining their boundaries. Neither subsumes the other.

The Sixty-Year Fork

The history of computing contains two parallel visions. In 1956, William Ross Ashby coined "intelligence amplification" in cybernetics. In 1960, J.C.R. Licklider proposed "Man-Computer Symbiosis." Then in 1963, Engelbart published his framework arguing that technology should amplify human capabilities rather than simulate human intelligence.

Engelbart's key insight: "Accepting the term 'intelligence amplification' does not imply any attempt to increase native human intelligence. The term 'intelligence amplification' seems applicable to our goal of augmenting the human intellect in that the entity to be produced will exhibit more of what can be called intelligence than an unaided human could."

Meanwhile, the AI research community took a different path—building autonomous systems that replicate human reasoning. John Markoff later identified this as the fundamental split: AI (artificial intelligence) versus IA (intelligence augmentation). Engelbart was firmly in the IA camp.

Both approaches produced valuable technology. But they optimize for different outcomes.

The Centaur Lesson

After losing to Deep Blue in 1997, chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov didn't retreat from computers. He invented a new form of chess where humans partner with machines instead of competing against them—Advanced Chess, also called Centaur Chess.

The results upended assumptions about human-AI collaboration.

In a 2005 online tournament, the winning team wasn't grandmasters with supercomputers. It was two amateurs with three weak computers. Their advantage: a superior process for human-machine collaboration. When their AIs disagreed, the humans investigated those moves further.

Kasparov's conclusion: "Weak human + machine + better process was superior to a strong computer alone and, more remarkably, superior to a strong human + machine + inferior process."

While one tournament doesn't prove a universal rule, it points toward a pattern that later research confirmed: the critical variable often isn't the power of either participant—it's the quality of their collaboration.

Process Over Power

Most AI development focuses on capability. Bigger models, more parameters, faster inference. The centaur lesson suggests we should invest equally in collaboration design.

Research from Harvard Business School confirms this pattern. In a study of consultants using AI, participants completed 12.2% more tasks, finished 25.1% faster, and produced 40%+ higher quality results. But the researchers identified something unexpected: AI capabilities create a "jagged technological frontier."

Some tasks that seem easy for AI fail unexpectedly. Other tasks that seem difficult succeed. The frontier doesn't map to human intuitions about difficulty.

The researchers also observed two collaboration patterns:

- Centaurs divide and delegate—some tasks go to AI, some stay with the human

- Cyborgs fully integrate their workflow with continuous AI interaction

Both patterns showed productivity gains, though the study didn't determine which approach worked better across all contexts. This reinforces the jagged frontier finding: there's no single right approach. A framework that supports both styles—and makes it easy to experiment with different human-AI splits—can adapt to the unpredictable nature of AI capability boundaries.

The 0.5% Multiplier Effect

Here's the evidence that changed how I think about human-AI collaboration.

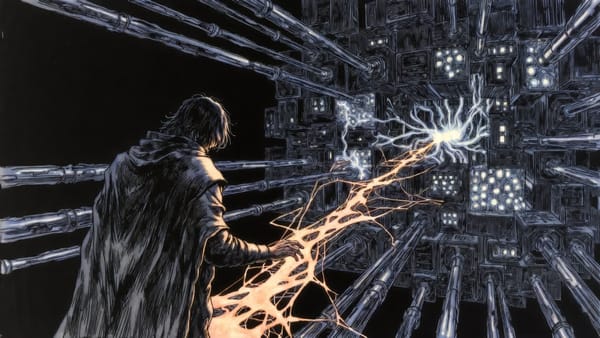

In a clinical study detecting lymph node cancer cells, AI alone achieved 7.5% error rate while human pathologists achieved 3.5%. The humans were better—but not by much.

Combined, they achieved 0.5% error rate.

That's approximately 15x lower error rate than AI alone, and 7x lower than humans alone. The improvement wasn't additive—it was synergistic. The combination produced something neither could achieve independently.

This happens when:

- Roles are clearly defined (humans excel at judgment, AI at pattern recognition at scale)

- Collaboration protocols exist (structured handoffs, not ad-hoc queries)

- Trust is calibrated (knowing when to defer to each other)

Why "Adjacent" Matters

Common framings carry implicit assumptions:

- "Augmented Intelligence" implies modification OF human intelligence

- "AI Assistant" implies hierarchy—AI serves the human

- "Copilot" implies the human is still flying

"Adjacent" implies spatial relationship. Working alongside, not inside or subservient. The framework isn't trying to make you smarter or do your job for you. It works next to you, at your shoulder, contributing what it does well while you contribute what you do well.

This isn't just semantics. It shapes architecture.

When you design for augmentation, you build tools that modify human capability. When you design for assistance, you build tools that respond to commands. When you design for adjacency, you build tools that maintain clear boundaries while enabling collaboration across those boundaries.

The Cognitive Offloading Warning

There's a danger to AI collaboration that research is starting to document.

A 2025 study of 666 participants found significant negative correlation between frequent AI tool usage and critical thinking abilities. The researchers identified cognitive offloading—delegating mental work to external resources—as a potential mediating factor, though the study's correlational design can't rule out reverse causation (people with weaker critical thinking skills may simply rely more on AI).

The pattern was age-dependent. Younger users (17-25) showed higher AI reliance and lower critical thinking scores. Older users (46+) maintained stronger critical thinking with less AI dependence. Higher education served as a protective buffer—suggesting that foundational thinking skills may help users engage with AI more critically.

This isn't an argument against AI tools. Cognitive offloading to notebooks, calculators, and computers has always extended human capability. The warning is about passive consumption versus active collaboration.

MIT economist David Autor puts it well: "Tools often augment the value of human expertise. They shorten the distance between intention and result."

But collaboration requires calibrated trust. In a CheXpert study of radiology AI, radiologists working WITH the tool actually made MORE errors than those working alone—because they didn't know when to trust the machine. Compare this to the lymph node study where structured collaboration achieved 0.5% error rates: the difference appears to be trust calibration, not collaboration itself.

The distinction matters: the risk isn't AI assistance per se—it's AI assistance without clear protocols for when to defer and when to override.

Anti-Deskilling Architecture

The Intelligence Adjacent framework attempts to embody these principles through specific design choices. Whether they succeed is something users will determine, but here's the philosophy behind the architecture:

Transparent reasoning, not black boxes. When the framework produces output, you see how it got there. Skills document their methodology. Agents explain their routing decisions. The goal isn't magic—it's traceable logic.

Editable outputs, not final answers. Everything the framework produces is a draft. You review, modify, approve. The human remains the author even when AI accelerated the process.

Skill documentation as knowledge transfer. Skills aren't just capability—they're encoded expertise. Reading a skill file teaches you the methodology, not just how to invoke it. The framework documents the "why" behind the "how."

Dynamic initiative, not request-response. Stanford HAI research identifies four hallmarks of effective human-AI systems: dynamic initiative switching (either party can propose, question, or defer), negotiation of roles (responsibilities continuously re-allocated), complementary strengths (humans provide judgment, AI provides scale), and transparency (each side models the other's goals).

Most AI tools are request-response. You ask, it answers. That's lookup, not collaboration. True collaboration requires AI that can question your assumptions and humans that can override AI suggestions.

The Security Professional Context

I built this framework for security work, where the stakes make these principles non-negotiable.

Security requires judgment you can't outsource. When you sign a penetration test report, your professional reputation is on the line. When you advise a client on risk, you're accountable for that guidance. AI can accelerate research, recognize patterns at scale, and generate documentation—but the human must remain the decision-maker.

The framework handles:

- Research acceleration (gathering sources, identifying patterns)

- Pattern recognition at scale (analyzing configurations, scanning for vulnerabilities)

- Documentation generation (reports, findings, recommendations)

The human handles:

- Risk judgment (what matters in this context?)

- Ethical decisions (should we proceed?)

- Accountability (whose name goes on this?)

This isn't limitation—it's appropriate role definition. The centaur model works because each participant does what they do best.

Building Adjacent

If you're building AI systems, the adjacent philosophy suggests different design priorities:

Invest in process design. The collaboration protocol matters more than raw capability. How do handoffs work? When does the human intervene? How is trust calibrated?

Support experimentation. The jagged frontier means you can't predict which tasks work. Build frameworks that make it easy to try different human-AI splits.

Document the reasoning. If users can't see how outputs were produced, they can't calibrate trust. Transparency enables the kind of collaboration that produced the 0.5% error rate.

Preserve human skill. Design for the 80/20 split—automate the routine, amplify the critical. If your tool makes users worse at their core job over time, you've built the wrong thing.

Maintain boundaries. Adjacent means sharing an edge, not merging. Effective collaboration happens when both parties understand their distinct contributions.

The goal isn't AI that replaces human expertise. It's AI that works alongside human expertise to achieve outcomes neither could reach alone.

That's what Intelligence Adjacent means.

Get the Full Framework

Create a free account to access all framework documentation and implementation guides.

Sources

Historical Foundations

- Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework (Engelbart, 1962)

- Intelligence Amplification - Wikipedia

- AI as Cognitive Amplifier: Rethinking Human Judgment (arXiv)

Centaur Chess and Human-AI Collaboration

- How To Become A Centaur (MIT Journal of Design and Science)

- Advanced Chess - Wikipedia

- The Centaur Programmer (arXiv)

Productivity and Knowledge Worker Research

- Navigating the Jagged Technological Frontier (Harvard Business School)

- How Generative AI Can Boost Highly Skilled Workers' Productivity (MIT Sloan)

- AI Should Augment Human Intelligence, Not Replace It (Harvard Business Review)

Human-Centered AI Design

- Human at the Center: A Framework for Human-Driven AI Development (AI Magazine)

- Beyond Automation — The Case for AI Augmentation