The Demographic Time Bomb: Why Declining Birth Rates Are Reshaping Economics and Security

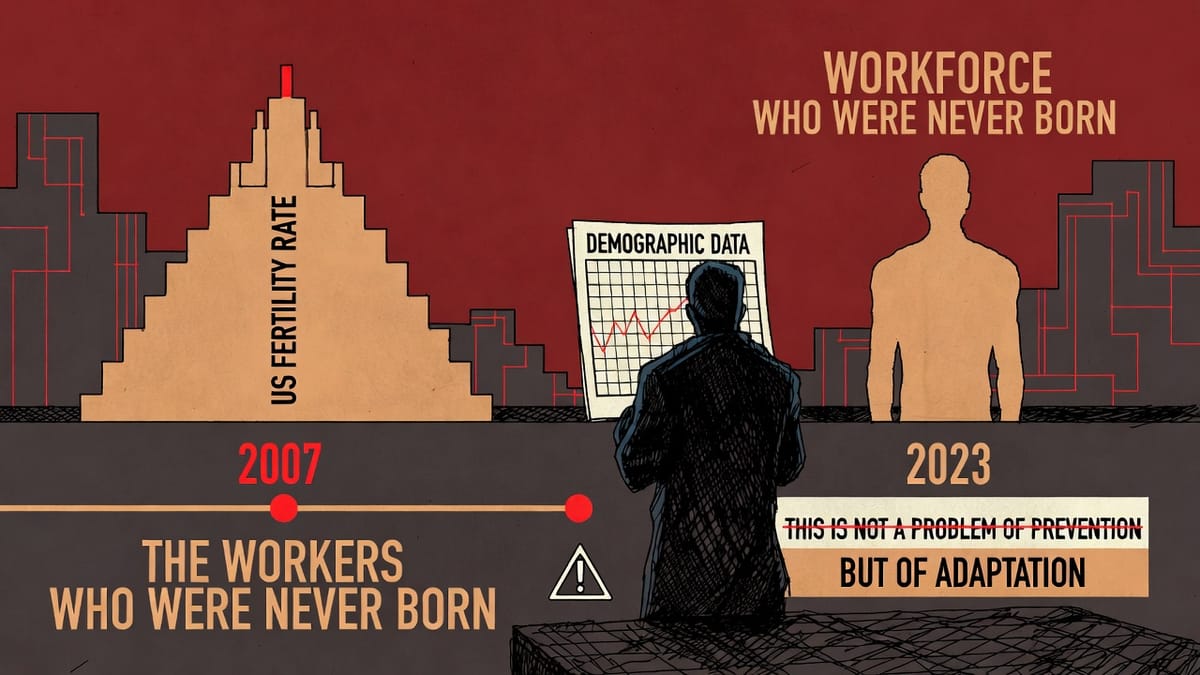

US fertility fell below replacement in 2007. The workers who would sustain our economy were never born. We're not preventing a crisis - we're adapting to one.

title: "The Demographic Transition Has Already Happened: An Economic Reality Check"

slug: "demographic-transition-economic-reckoning"

excerpt: "US fertility fell below replacement in 2007. The workers who would sustain our economy were never born. Augmentation, not replacement, is the architecture for scarcity."

status: "draft"

visibility: "public"

tags: ["tools", "ai-systems", "security"]

category: "research"

scheduled_for: "2025-12-31T12:00:00Z"

The fertility decline that drives demographic concerns isn't coming - it's been here since 2007. The consequences are unfolding now.

In 2007, the United States fertility rate dropped below the 2.1 replacement level and never recovered. Fewer children were born between 2008 and 2025 than needed to sustain our workforce, fund our entitlements, and drive our economy. Immigration has historically offset a portion of this deficit - net migration added approximately 1.1 million people annually in 2022-2024 - but sustaining current worker-to-beneficiary ratios would require immigration levels 2-3x higher than current rates.

This creates an 18-25 year lag between fertility decisions and workforce entry. The 2007 fertility drop translates to workforce shortfalls beginning around 2025-2032 - the crunch we're entering now.

By 2024, the US fertility rate hit an all-time low of 1.599 children per woman. This isn't a trend to reverse - it's a demographic reality that's already locked in for the next two decades. The workers who will (or won't) enter the labor force in 2043 have already been born. Or not.

This post examines what that reality means for our institutions, our economy, and how we work. The numbers are sobering, but the path forward requires clear-eyed analysis, not panic.

The Demographic Arithmetic

Every discussion of demographic decline eventually becomes political. Fertility policies, immigration debates, entitlement reform - these trigger ideological reflexes that obscure the underlying arithmetic. Let's start with the numbers - worker-to-beneficiary ratios that constrain policy options regardless of political approach.

The worker-to-beneficiary ratio tells the whole story. In 1960, there were more than five workers paying into Social Security for every beneficiary. By 2024, that ratio dropped to 3:1. It's projected to fall below 2.5:1 within a generation.

Eleven thousand baby boomers turn 65 every single day - a calculation based on birth certificates, not forecasts. The 76 million Americans born between 1946 and 1964 are now aging through the system, and the generations behind them are substantially smaller.

The Census Bureau projects that annual deaths in the US will reach 3.6 million by 2037 - one million more than in 2015. Deaths will rise every year, peaking in 2055. Without immigration, the Congressional Budget Office projects the US population will start shrinking within five years, when deaths surpass births.

These are demographic projections based on birth records and actuarial models.

The Global Pattern We're Following

The United States is not uniquely affected. It's part of a global pattern that's accelerating faster than most projections anticipated.

The Lancet projects that by 2050, over three-quarters of countries will not have high enough fertility rates to sustain their populations. By 2100, that rises to 97% of all countries. Between 2019 and 2024, only 12 countries saw fertility rates increase while 185 saw decline or stagnation.

The most extreme cases offer a preview of what's coming:

South Korea declared itself a "super-aged" society in December 2024, meaning over 20% of its population is now 65 or older. Its fertility rate of 0.74 children per woman is the world's lowest. The Bank of Korea's governor stated plainly: "If the fertility rate remains at 0.75, Korea will inevitably face prolonged negative economic growth after 2050."

South Korea spent $270 billion over 16 years on childbirth incentives. The result: fertility continued falling.

Japan offers an even longer case study. What began as the "Lost Decade" in the 1990s extended to the "Lost 20 Years" in the 2000s, then the "Lost 30 Years" through the 2010s - and the pattern continues. From 1991 to 2003, the Japanese economy grew only 1.14% annually.

While demographic decline correlates strongly with Japan's stagnation, multiple factors contributed: the asset bubble collapse (1991), delayed monetary response, banking system weakness, and cultural resistance to immigration. Demographics amplified these structural issues but wasn't the sole cause. The conventional narrative attributes Japan's stagnation to the asset bubble collapse and policy mistakes. But demographic decline was a "frequently overlooked" structural cause, according to Asian Development Bank analysis. Japan's aging workforce drove down productivity, reduced innovation, and created a vicious cycle where economic uncertainty led to delayed marriage and fewer children, worsening the demographics further.

China, despite reversing its one-child policy in 2016 and allowing three children in 2021, now faces a fertility rate around 1.0-1.2 - among the lowest globally. The UN projects China's population could fall below 800 million by 2100 - nearly half its current size.

Why the "Three Crises" Are Really One

Political discourse treats Social Security, Medicare, and the national debt as separate problems requiring separate solutions. They're not. They're symptoms of a single underlying cause: the ratio of workers to dependents. While immigration, productivity gains, and fiscal reforms can help address these pressures, the fundamental constraint is demographic.

Social Security's trust fund is projected to be depleted by 2033-2034, according to the 2025 Trustees Report. At that point, retirees face an automatic 19-23% benefit cut under current law. The 75-year shortfall is 3.82% of taxable payroll - the largest since 1977.

Fixing this through financial mechanisms alone would require either a 22% cut to benefits for all current and future beneficiaries, or a 29% increase in payroll taxes, or some combination.

But here's what those numbers obscure: you can't tax workers who don't exist.

The national debt reached $38 trillion in October 2025. Interest payments now exceed $882 billion annually - more than the federal government spends on national defense or Medicare. While the debt explosion stems from multiple factors (COVID spending, wars, tax cuts, entitlement growth), the demographic shift exacerbates it by shrinking the future tax base needed to service this debt. The Penn Wharton Budget Model estimates that financial markets cannot sustain more than 20 years of accumulated deficits under current fiscal policy.

By 2027, debt is projected to reach 106% of GDP - its historical high. If unaddressed, it will reach 200% of GDP by 2047.

Medicare costs are driven by an aging population that requires more medical care. According to OECD data, public social spending across member countries increased from about 11% of GDP in the early 1990s to about 22% by 2018, with the majority driven by pensions, healthcare, and long-term care for aging populations.

Three problems, one root cause: fewer young people supporting more old people. Financial engineering can delay or mitigate the problem, but it cannot change the underlying worker-to-beneficiary arithmetic.

The College Enrollment Cliff Is Just the Beginning

The most visible institutional impact is already hitting higher education. The number of 18-year-old high school graduates will peak in 2025 at around 3.9 million, followed by a 15-year decline. By 2041, the number of traditional-age incoming college students will be down 13%.

This isn't theoretical. In the first half of 2024, more than one college per week announced closure. The Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia projects the pace of closures will accelerate.

The impact is geographically concentrated. 38 states will see enrollment declines:

- Illinois: -32%

- California: -29%

- New York: -27%

- Michigan: -20%

- Pennsylvania: -17%

Two-year public colleges have already lost 38% of their enrollment between 2010 and 2022. Two-year private for-profit colleges lost 59%.

College enrollment is just the first institutional impact. The same demographic curve reshapes the entire economy:

- Healthcare - fewer young nurses and doctors entering the profession while demand from aging patients increases

- Housing - fewer family formations, shifting demand patterns, potential price corrections in areas dependent on population growth

- Consumer goods - smaller target markets, reduced aggregate demand

- Tax base - fewer workers generating the income and payroll taxes that fund everything else

The institutions we built for the 20th century were designed during an era of consistent population growth. That growth pattern has now reversed.

The Economic Drag Is Already Measurable

Research from the American Economic Association quantifies the damage: each 10% increase in the fraction of the population age 60+ decreases per capita GDP by 5.5%. One-third of this reduction comes from slower employment growth. Two-thirds comes from slower labor productivity growth.

Population aging reduced GDP per capita growth by 0.3 percentage points per year during 1980-2010. NBER researchers found that OECD countries would have grown by 2.8% per year instead of 2.1% without these demographic headwinds.

The labor market effects are already visible. The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta found that in 2022, the prime-age worker population (ages 25-54) increased by just 40,000 while the number of Americans 65 and older jumped by 2 million. Aging population is a major reason for worker shortages that have helped fuel inflation.

Monetary policy can influence economic activity but cannot change the size of the workforce that was born 18-25 years ago. Central banks face structural constraints from demographics that conventional policy tools cannot overcome.

The Fiat Currency Problem

These economic pressures have monetary implications that receive less attention: the relationship between demographic decline and monetary stability.

Fiat currency's value ultimately rests on productive capacity. Productive capacity requires workers. Currency value ultimately depends on what an economy can produce and trade. Fewer workers producing goods and services means less real economic output backing each dollar in circulation. While central banks can adjust money supply and interest rates to manage inflation in the short term, demographic decline creates persistent structural pressure - the Fed can influence demand, but cannot increase the supply of workers who don't exist.

The Federal Reserve's balance sheet tells the story of how we've responded to stagnation. Pre-2008, it stood at approximately $900 billion. It peaked at $8.9 trillion in April 2022 - nearly nine times the pre-crisis level. As of late 2025, it remains around $7.2 trillion.

Central banks globally appear to recognize the vulnerability. According to World Gold Council data, net official gold purchases exceeded 1,100 tonnes in 2022 and remained above 1,000 tonnes in both 2023 and 2024 - a clear hedge against fiat currency risks.

The trap is this: you can print money, but you cannot print workers. You can lower interest rates, but you cannot raise birth rates retroactively. The financial system is built on growth assumptions that the demographic system can no longer deliver.

Federal debt has surpassed $38 trillion, representing a debt-to-GDP ratio exceeding 120% - past the 100% threshold economists identify as a sustainability benchmark. This debt must be serviced by a shrinking tax base. The arithmetic is unsympathetic.

Can AI Fill the Gap?

This brings us to the question everyone is asking: can artificial intelligence and automation offset demographic decline?

The honest answer is: partially, eventually, but not fast enough.

Current data shows AI adoption accelerating. The Dallas Fed reports that 26.4% of workers used generative AI at work in the second half of 2024. The share of US firms using AI rose from 3.7% in late 2023 to 10% by September 2025. AI-related business investment is surging at an 18% annualized rate.

Upskilling existing workers can partially offset demographic constraints. The Dallas Fed estimates workforce education and training improvements contributed 0.15-0.2 percentage points to annual productivity growth historically. However, these gains are incremental compared to the scale of demographic headwinds (0.3+ percentage point GDP drag annually).

But the productivity gains haven't materialized yet. The Penn Wharton Budget Model estimates AI's impact on total factor productivity remains small today - just 0.01 percentage points in 2025 - because most businesses haven't fully adopted the technology.

Their projections suggest AI will increase GDP by 1.5% by 2035, nearly 3% by 2055, and 3.7% by 2075. The Dallas Fed's reasonable scenario suggests AI might boost annual productivity growth by 0.3 percentage points for the next decade.

However, technology adoption curves can accelerate non-linearly. The internet reached 50% US adoption in 7 years (1997-2004). Smartphones took 5 years (2007-2012). If GenAI follows mobile adoption patterns rather than historical productivity tool curves, meaningful economic impact could arrive sooner than linear projections suggest.

The counter-pressure: most productivity gains require workflow redesign, not just tool adoption. This organizational change happens slower than technology deployment.

This creates a timing problem. The demographic pressures are intensifying now, with Social Security trust funds depleting in 2033 - just eight years away. The AI productivity gains, meanwhile, accrue over decades. Meaningful AI GDP impact arrives around 2035-2055 - after the immediate fiscal crisis hits.

There's also an adoption gap. Nearly 90% of companies say they've invested in AI technology, but fewer than 40% report measurable gains. The reason: most workflows were designed for a pre-AI world. Applying AI to individual tasks within legacy processes doesn't deliver the productivity gains now possible.

As McKinsey's research notes, realizing AI productivity gains requires redesigning entire workflows so that people, agents, and robots can work together effectively.

Augmentation, Not Replacement

Here's where the standard "AI will replace workers" versus "AI will create new jobs" debate becomes irrelevant. We don't have enough workers to replace OR to create new jobs for.

The most promising near-term path is augmentation - making each human worker substantially more productive through AI partnership. This doesn't preclude other approaches but offers the fastest route given current constraints.

This isn't just a design philosophy. It's a demographic necessity.

Chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov discovered something surprising when humans and computers teamed up: "Weak human + machine + better process was superior to a strong computer alone and, more remarkably, superior to a strong human + machine + inferior process."

The key variable wasn't the strength of the human or the power of the computer. It was the quality of the process that connected them.

Research on human-AI augmentation confirms this distinction matters for economic outcomes. While automation involves direct task transfer from humans to machines, augmentation occurs when using a machine increases worker productivity in that task or other tasks. The effects on labor markets are countervailing - automation can displace workers, but augmentation can increase their value.

Schneider Electric's president of North American operations stated it directly: "There's just not enough people in the U.S. If we're going to keep the GDP growth we require, we're going to need to find ways to engage people differently."

We face constraints on each path: hiring is limited by birth rates from 18-25 years ago, full automation faces adoption timelines measured in decades, and augmentation offers the most promising near-term approach given these constraints.

What Adaptation Looks Like

This isn't a call for doom. It's a call for adaptation.

Japan's 30-year experience offers lessons - both positive and negative. The negative: they treated demographic decline as a temporary problem to be solved through monetary policy and refused serious immigration reform (the ADB notes it remained "taboo"). The positive: Japanese society adapted. Crime remained low. Social cohesion held. Quality of life remained high by global standards.

The United States has advantages Japan didn't: a more flexible labor market, greater immigration (historically), a stronger culture of entrepreneurship, and potentially, AI arriving just as the demographic crunch peaks.

The United States has historically relied on immigration to supplement birth rates. Net migration added approximately 1.1 million people annually in 2022-2024. However, sustaining current worker-to-beneficiary ratios would require immigration levels 2-3x current rates - politically contentious and logistically challenging given global fertility decline reducing source country populations.

The necessary adaptations include:

Institutional redesign. Universities, healthcare systems, pension structures, and real estate markets built for population growth need to be restructured for population stability or decline. The institutions that adapt first will outcompete those that wait.

Workflow transformation. The 90% of companies that have invested in AI but see no gains need to move from "applying AI to existing tasks" to "redesigning workflows for human-AI collaboration." This is the difference between a productivity increment and a productivity multiplication.

Realistic fiscal planning. The growth assumptions embedded in virtually every economic model, financial product, and institutional plan need to be updated. Pensions, endowments, and government budgets that assume perpetual growth will face reality eventually. Better to face it deliberately.

Human-AI architecture. When humans become scarce, you can't replace them wholesale. You must multiply what each one can accomplish. Systems that augment human capability rather than attempting to substitute for it will be the architecture of a constrained future.

The Intelligence Adjacent Thesis

This is why the mission of Intelligence Adjacent - building systems that augment human intelligence, not replace it - isn't just a design philosophy. It's the correct architecture for the demographic reality we're entering.

The IA Framework implements this through specialized agents and modular skills that multiply human capability rather than attempting wholesale replacement. When facing complex tasks - security testing, content creation, compliance analysis - the framework routes work to domain-specialized agents that augment human decision-making rather than bypassing it.

The fertility rate that dropped below replacement in 2007 already determined the workforce of 2025-2043. Those workers were never born. They cannot be hired.

But the humans we do have can be augmented. A single security professional can conduct enterprise-grade penetration testing. A single writer can produce research-backed content at scale. A single engineer can implement infrastructure hardening across multiple compliance frameworks. Not through automation that eliminates the human, but through augmentation that multiplies what each human can accomplish.

The systems we build to accomplish this will define whether the next thirty years look like Japan's stagnation or something more dynamic.

The Path Forward

The arithmetic is clear: fewer workers supporting more retirees creates structural economic pressure. No single solution - immigration, automation, or productivity gains - solves this alone.

The viable path combines:

- Realistic fiscal adjustment to entitlement programs reflecting demographic reality

- Human-AI augmentation to multiply individual worker productivity

- Institutional redesign for stability rather than perpetual growth assumptions

- Selective immigration to supplement (not replace) domestic workforce

The demographic transition is happening regardless of policy choices. The question is whether institutions adapt proactively or face crisis-driven change.

Systems built to augment human capability become necessity, not philosophy, in a world where human talent is the constraint. This is why frameworks like Intelligence Adjacent focus on agent-based augmentation - routing complex tasks to specialized AI agents that extend human capability rather than attempting wholesale automation.

When you can route security analysis to a specialized agent, generate research-backed content through a writing agent, or orchestrate compliance workflows through domain-specific intelligence - you multiply what each human can accomplish without replacing their judgment.

The fertility decline has already happened. The reckoning is unfolding. The question is whether we adapt deliberately or are adapted to unwillingly.

The arithmetic doesn't negotiate. But within those constraints, there's still architecture to be chosen.

Intelligence Adjacent builds systems that augment human capability rather than replace it - the correct architecture when talent becomes the constraint. If this analysis was useful, consider joining as a Lurker (free) for methodology guides, or becoming a Contributor ($5/mo) for implementation deep dives and to support continued development.

Sources

Global Demographic Data

- The Lancet: Dramatic Declines in Global Fertility Rates

- Our World in Data: The Global Decline of Fertility Rate

- Our World in Data: Peak Global Population - 2024 UN Revision

- Visual Capitalist: Mapped - Every Country by Total Fertility Rate

US Demographics

- CBS News: U.S. Birth Rate Hits All-Time Low

- PBS News: U.S. Fertility Rate Reached New Low in 2024

- PMC: Decreasing Fertility Rate in the United States

Baby Boomer Demographics

- U.S. Census Bureau: As Population Ages, U.S. Nears Historic Increase in Deaths

- PMC: The 2030 Problem - Caring for Aging Baby Boomers

- ABC News: A Look at Aging Baby Boomers

Social Security and Entitlements

- Social Security Administration: 2025 OASDI Trustees Report

- Bipartisan Policy Center: 2025 Social Security Trustees Report

- CRFB: Analysis of 2025 Social Security Report

National Debt and Fiscal Policy

- U.S. GAO: America's Fiscal Future

- Penn Wharton: When Does Federal Debt Reach Unsustainable Levels?

- Fortune: America's $38 Trillion National Debt

College Enrollment

- NPR: A Looming 'Demographic Cliff'

- Inside Higher Ed: College-Age Demographics Begin Decline

- Brookings: Fewer Freshmen Enrolled

Economic Impact of Aging

- American Economic Association: Effect of Population Aging on Growth

- NBER: Implications of Population Aging

- Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta: Aging and the Labor Market

AI and Productivity

- Penn Wharton: Projected Impact of Generative AI on Productivity

- Dallas Fed: Advances in AI Will Boost Productivity

- EY: AI-Powered Growth

Human-AI Augmentation

- PMC: Human Augmentation, Not Replacement

- Harvard Business Review: AI Should Augment Human Intelligence

- MIT Sloan: AI More Likely to Complement Workers

- McKinsey: Work Partnerships Between People, Agents, and Robots

East Asia Case Studies

- ADB: Japan's Lost Decade - Lessons for Other Economies

- CNBC: South Korea's Birth Rate Collapse

- Morgan Stanley: South Korea Population Decline Crisis

Monetary Policy and Currency

Labor Market and Automation

Don't Miss the Next Post

Subscribe for free to get updates on AI architecture and intelligent systems.